Tying the Hatch

One of the most rewarding accomplishments in fly fishing is when everything comes full circle. When you have a good understanding of fish lies, behavior, hatches, feeding rituals, and knowledge to catch fish, your adventures into fly fishing and tying become magnified. One of my favorite rituals as a fly tier is to read about, study, and tie a hatch through its entire life cycle. During intense hatches, trout will feed and move along with the stages of the hatch. What they are feeding on one minute may change in a flash as fish will keep up with the speed of the hatch. Having the right flies for a certain stage of the hatch will keep you dialed into the fish, and being a successful angler during all stages is a true reward. What I am touching on here only scratches the surface of the different species and life cycles to tie. Below I’ll be talking mostly about the midge and mayfly lifecycles as a reference of how to approach and tie the hatch. Whatever hatch you are tying, applying this approach will hopefully help you on the vise!

Life Cycles

Bugs go through different life cycles at different times but all have their similarities. The maturation of a bug from larva or nymph to adult is a basic cycle to most aquatic insects. As fly tiers, we need to differentiate bug species and study how species look and act during stages of their hatch. For example, a mayfly looks totally different than a stonefly but both have similarities in their life cycle. They start as a nymph, swim to the surface (mayfly) or crawl to the banks (stonefly), and hatch as an adult. When tying the life cycle you will typically be imitating one of these stages and applying different techniques from species to species to best match bug behavior.

Tying from the Stream Bottom to the Surface

If you’ve looked at life cycle drawings and charts you will notice there is a beginning and an end to the story, and a wonderful circle of life. When sitting down to tie a hatch I like to start from the beginning, the most immature stage of the bug gradually working up to the adult. By doing this, each bug you tie is a spring board into the next, and really gives you a good understanding of what key elements in each stage need to be imitated on the vise for success.

Understanding Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is defined as the process of transformation from an immature form to an adult form in two or more distinct stages. Some bugs go through complete and incomplete metamorphosis. Midges and mosquitos are a good example of a bug which goes through complete metamorphosis, egg to larvae, larvae to pupa, pupa to adult. Mayflies and stoneflies are good examples of a bug which goes through incomplete metamorphosis, egg to immature nymph, mature nymph to adult.

Larvae:

When hatches are dormant or not imminent, the larvae stage of a bug can be a mainstay in the trout’s diet. The main job as larvae is to eat and grow, and during this time the larvae will shed or molt and eventually develop into pupa. Let’s take a look at a few key elements to consider when creating our imitation on the vise.

Behavior: Larvae are mainly bottom dwellers because that’s where the food is located. Sometimes larvae will venture into the water column for suspended food like algae. Larvae can be found along the entire river bottom shallow to deep. They move along the bottom very slowly and try to stay hidden from predators such as larger nymphs and fish.

Presentation: Larvae can be found shallow to deep, therefore tying larvae weighted and un-weighted can be key. Weighted larvae imitations are made to get down, and a good tungsten weighted fly will get you down even in the faster currents where larvae still live. I also like to carry un-weighted larvae for shallow fishing. As fish feed and move into shallow lies, its key to present a fly which will drift and bounce naturally along the bottom. Fishing heavily weighted flies shallow get the fly stuck and has greater chances of catching moss, two factors which can spook a fish and send him back to the depths.

Elements on the Vise: There are hundreds of imitations for larvae out there, and the most effective have an attractive fish allure about them. Here a few suggestions to consider when tying larvae imitations:

- Size and Profile: The size and profile of larvae differentiate from species to species. For example, some midge larvae can be as small as a size 28 hook, and some caddis larvae can be tied all the way into an 8 or 10. Be sure to study the natural insect in your river for size and profile first. Trout are very accustomed to what’s in their river. Larvae patterns that work on some drainages might not work in yours.

- Stick out from the rest: As fly fishers, we always have to remember that we are competing with thousands of naturals below the surface, so how do we get the fish to take our offering? Simply adding a bead or an element of flash to your patterns will make it stand out from the rest and often entices a fish to come check your offering. With that being said, be careful about adding too much, remember fish still have to think it’s real before taking the fly.

Pupa and Nymphs:

Both different, the nymph and pupa stage of insects share similarities in the way we tie and fish them. During the nymph or pupa stage, the bug continues to eat and grow and will start to show signs it’s ready to hatch. Let’s take a look at these signs and how to imitate them on the vise.

Behavior: During the nymph and pupa stages, bugs become much more active in the water column and on the stream bottom. They will tend to dart and bend and are quite noticeable as they travel amongst the vegetation. When the bug matures and is about to hatch, these insects will often “let go” from the rocks and vegetation to settle where hatching conditions are right, this is a form of phenomenon called behavioral drift and bugs do it at different times for various reasons.

Presentation: Nymphs andpupa can often be found shallow or deep like the larvae, and upon accent, swim to the surface to hatch. So just like the larvae, weighted and un-weighted imitations both play a key role in presentation. Some pupa, like chironomids, which are found mostly in stillwaters, look and act different from a nymph. For example, the correct presentation for a chironomid is typically vertical; this is because the pupa does not have to put up with stronger currents like nymphs in rivers. Instead they have the freedom to explore the water column while darting in and out of the weeds for protection. Nymphs, on the other hand, are flat with longer legs for dealing with currents. They hide and cling to the bottom substrate and feed on the vegetation from the rocks. Typical presentation for a nymph is bouncing and crawling the imitation along the bottom with or without indicator until emergence is imminent.

Elements on the vise: There are certain signs to watch for when fishing which will tell you if a hatch is close, and you can bet the trout know too. These telltale signs need to be addressed on the vise if you are going to be successful fishing the hatch.

- Size and Profile: The size and profile of the bug you are imitating always comes first. Before we address other hatching characteristics always make sure you’re working with the right size and profile to begin. As a trout swims looking for food, we want to make sure our bug fits in with the rest.

- Physical Signs: During the pupa and nymph stage, bugs are going through a lot of changes, they molt and grow and ultimately exhibit very noticeable characteristics. For example, pupa and nymphs will develop dark wing pads when reaching full maturity. Fishing a pattern which exhibits this at the right time can be absolutely deadly, and I’ve literally seen fish key in on this. It’s a good idea to collect stream samples during a hatch to see what an immature nymph or pupa looks like versus a ready to hatch insect to properly duplicate this on the vise.

- Legs: When nymphs let go of rocks or are moved from heavy currents, they will tend to drift with their legs splayed out in search of another rock to cling. Adding legs to your patterns is a definite fish attractor. From a trout’s perspective as a nymph floats by, it sees the general profile of the bug and the legs fluttering about in the current.

- Flash: Using an element of flash in your nymph patterns can be very effective. Typically, a piece of flash for the back or abdomen is enough to get the trout’s attention. I try to limit flash during this stage and only use it as an attractor; I want my fly to remain as a nymph. I find that if I use too much flash or legging material, I start to cross the line of nymph to emerger.

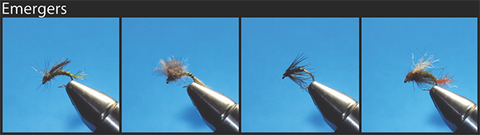

Emergers:

As the insect continues to grow, molt and shed, and matures to a hatch ready state, the next adventure is to emerge. Emergers are bugs which have left the bottom to ascend to the surface and hatch. Stoneflies are a little different and will actually crawl out of the water on the banks and cling to grass or rocks to crack open their shuck and hatch.

Behavior: When an insect emerges from the bottom, their behavior will be very aggressive. This is where they are most vulnerable to trout, suspended in the water column with nowhere to hide. Emergers will take a very aggressive swim to the surface for this reason, and during their accent will crack open their shuck and start to expose their wings. All this action is easily seen by the fish as the emerger catches light and flutters about. When they reach the surface, they complete the process by crawling out of the shuck and become an adult. They tend to sit on the water for a minute drying their wings and getting used to their new surroundings before taking off to mate.

Presentation: Fishing with emergers is one of my favorite stages of the hatch. During emergence, fish tend to get into frenzy and exhibit very aggressive feeding behavior. Imagine you’re a fish and all of a sudden there are thousands of ribeyes swimming to the surface, quick easy meals which make fish go crazy. As an angler, we can give action to our flies when fishing and tying them as well. When fishing an emerger, a slight lift or twitch of the rod tip will impart action on your flies and could trigger a strike. This is just one technique amongst many to imitate the bug swimming to the surface. When tying emergers, a combination of materials will certainly give action to the fly even when fishing dead drift. Let’s take a look at some of these key feature’s to duplicate on the vise.

Elements on the vise: Emergers are one of my favorite bugs to tie. Tying this stage of the hatch allows you more freedom with your materials to create lifelike movement. Using certain materials which capture light and flutter about will be a key element to address on the vise when tying emergers. Get your wire brush out and get messy!

- Materials and Movement: One of the most versatile and life like materials for tying emergers will be the use of natural fur and feathers in your pattern. Natural materials move and sway underwater and give action to the fly during dead drift. When tying with these materials, it’s helpful to get them wet first. If I’m exploring the use of a new material, I’ll place it in a glass of water and impart movement. Try playing with several different feathers and materials in this manner, all of them act a little different and seeing this first hand will open the avenue to fly tying creativity.

- Get Messy: During emergence, bugs will capture light shedding their shuck popping out immature wings and legs. This is a very messy and clumsy state for the bug and one which can be duplicated on the vise. Don’t be afraid to create a messy emerger. I like to use a soft hackling technique to give my emergers life. Materials such as CDC and ostrich herl are also excellent choices for creating movement underwater. Once the fly is tied, I also like to use a wire dubbing brush to pick out and frizz my fly, giving it a very buggy look.

- Flash: An element of flash is always helpful when tying emergers. When the bug nears the surface, it will start to capture light and especially so when the shuck physically separates itself from the body. Using flash will imitate this very accurately and makes your bug stick out from the other naturals you are competing with in the water.

Adults and Spinners:

Once a bug has emerged to the surface, it continues to crawl from its shuck freeing its wings and legs. The shuck is completely shed and discarded, wings stand upright, and now the bug is a full adult. Adults eventually molt into spinners where mating takes place mid-air creating the swarm. After mating females deposit their eggs, by dabbing their abdomens on the water, they eventually fall “spent” to the water’s surface as is the same with males.

Behavior Adults: After a complete hatch, the adult will only be on the water’s surface for a few seconds allowing their wings to dry before taking off. In some cases during emergence, something goes wrong, and the bug can become what we call a “cripple”. Cripples can have undeveloped or torn wings, or not be able to shed its shuck completely. The behavior of a cripple feels like a state of panic for the bug. Batting its wings and tumbling on the surface in hopes it will free itself before a trout takes notice. This behavior is something often imitated by anglers, twitching and skittering, or dead drift, and is just a couple methods of many to fish cripples.

Behavior Spinners: After hatching and leaving the water’s surface, the adults will gather in nearby trees. Here they will molt into what is called a spinner. Spinners are the last stage in the life cycle and are responsible for mating and laying eggs before they expire and fall to the water’s surface. These bugs are available to the trout after they die and only drift lifeless in the current. Size and profile with delicate presentation is key for fishing spinners.

Presentation, Adults and Spinners: Dry fly fishing is an art in itself. Watching an expert dry fly fisherman or fisherwoman delicately deliver his or her fly with a successful sip and hook up is pure education, it’s not easy. From a casting perspective, I like to deliver my fly to the fish first from upstream using the stack mend method. If fish are deliberately slashing at the surface, you could be seeing aggressive strikes on crippled adults. Caddis are also well known for aggressively skittering and causing viscous splashy strikes. In this case, fishing the first part of your cast dead drift and then swinging and skipping the pattern back to you can trigger viscous strikes. Presentation and tying this stage go hand in hand especially when tying cripples. I always like to have a glass of water next to me at the vise so I can plop my ties in to see how they will float or act on stream. Adults should float high and dry, and cripples can be a combination of slightly sub surface to surface. Spinners are tied with flat bi-plane wings and long tails to imitate the expired and free drifting state of the bug and float flat on the surface.

Elements on the vise:

- Adults: There a lot of things which make a good dry fly effective. For me, as with a lot of my tying, size and profile are first, and a correct ride on the surface second. Dry flies are mostly tied with natural feathers and hair for floatability. Keep this in mind if you are introducing a synthetic to your pattern. Sparse use of flash and other materials is key to keeping your fly riding high and dry. There are synthetics on the market which are made to float high as well, such as foam, winging materials, and certain types of dubbing, all of which can lend to tying a successful dry.

- Cripples: Cripples are usually tied so the bug sits partially sub-surface. The effect is a bug which has not hatched properly due to torn wings, immaturity, etc. This is key to tying a cripple and the most important element to address in my mind. Don’t be afraid to put a leg or wing out of place, this is what you’re trying to imitate.

- Spinners: Spinners are tied in many different sizes and colors according to species you are trying to match, but they all carry a common theme. Spinner’s wings will be clear and ride like a bi-plane on the water’s surface. These bugs are dead and all characteristics lay flat on the water without life. Because the bug can be difficult to see, I always try and incorporate a tiny indicator on my fly, ice dub, hot colored yarn, or foam often do the trick. Only put enough in the pattern for you to see, not the fish. On a good spinner pattern, fish will only see the silhouette of the spent wings, body, and tails.

Tying and fishing the hatch through its entire lifecycle and being successful at it will bring more fish to the net, and as stated in the beginning, brings fly fishing full circle. There is so much more to tying a fly than just looking at an example and trying to imitate it. Discussing presentation, behavior, and life cycles before you hit the vise will ultimately help you in creation and problem solving. As a signature designer, I cannot begin to create unless I have the knowledge, and I cannot tell you how many times I was able to spring new ideas at the vise by simply studying and understanding the lifecycle first.